I write like a lover, I write like one dead

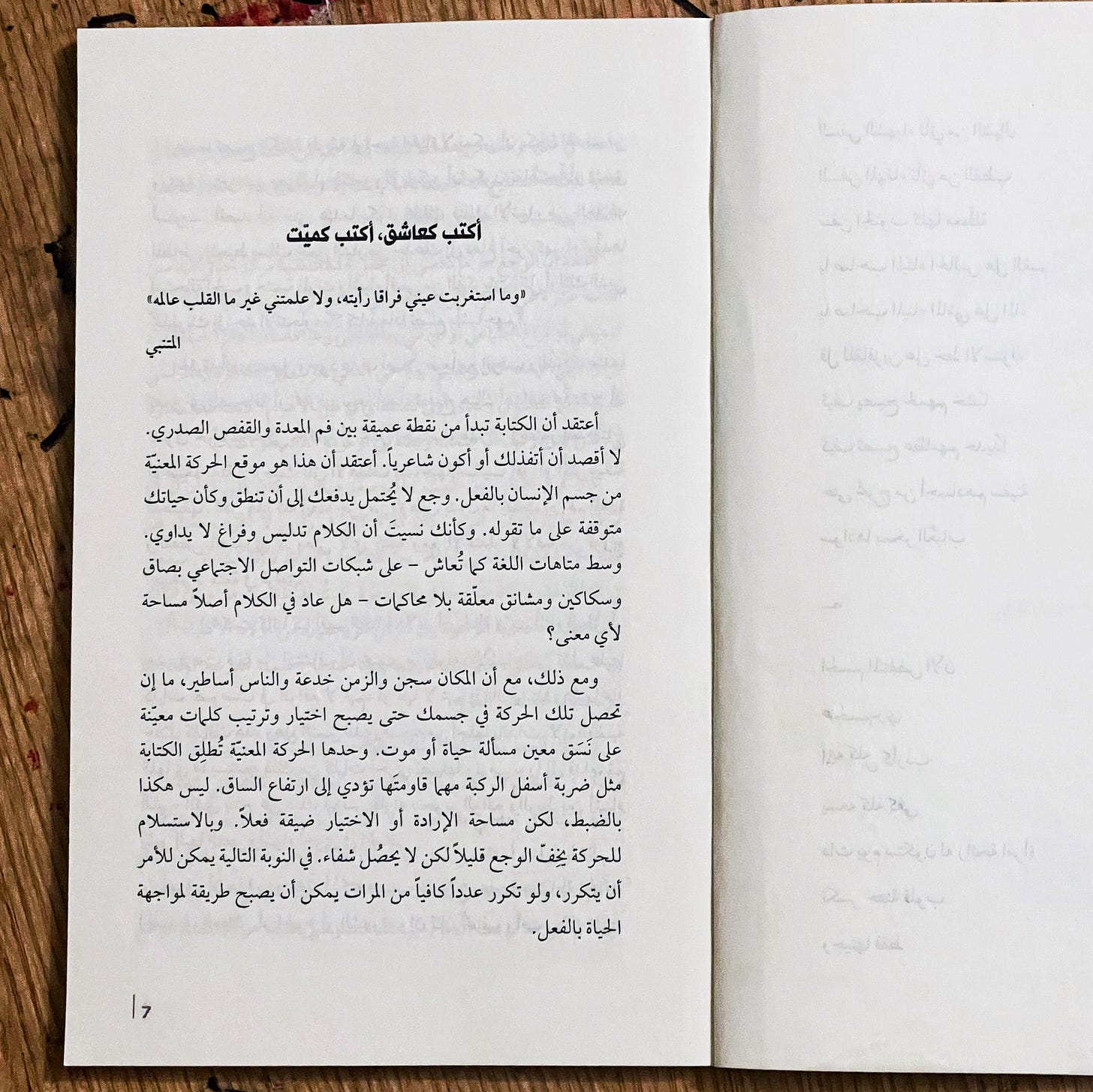

The opening essay of my second Mutanabbi book, translated by Robin Moger

All kinds of amazing things happened in 2022, and one of them was Robin Moger translating a blood-spatteringly personal essay I wrote while fiddling with my 2021 book of Mutanabbi riffs, And Yet My Heart: Third-Millennium Mutanabbi, two of which he also translated here and here. The piece opens another slim volume of essays and poems, And Yet My Heart: Post-Mutanabbi (aka Mutanabbi II), that was published in 2022. This is the first time it appears in English. May the soul of 2022 be gifted with mercy and light, as we pray for the dead here in Egypt. And a 2023 full of poetry and praise.

My eye not once surprised

at any parting that I saw,

nor taught me more

than that in which the heart is wise

- Al Mutanabbi -

I believe that writing starts at a point deep down between the mouth of the stomach and the ribcage. I don’t mean to sound like I’m reaching here, to be “poetic”: I truly believe that this is where the motion in question is located; an unbearable pain that drives you to speak, as though your very life depends on what you say. Like you’ve forgotten that speech is a scam, a nothing that solves nothing. Lost in the warrens of language as it is experienced on social media—spittle and knives and gallows thrown up without trials—is there any meaning left to speech at all?

But even so. Even though place is a prison and time is a trick and people fables, the instant that motion takes place in your body, the selection and arrangement of certain words to a certain form becomes a matter of life and death. That particular motion, like a sharp tap below the knee which, fight it all you like, will flick your leg up anyway. Well, not exactly that, but the space for agency, for choice, is genuinely diminished. And giving in to it might dull the pain but there’s never a cure.

The whole thing can happen again, and if it does, and happens enough, then it really can be a way to take on life. When writing becomes a way to take on life, the point of it cannot be to show off what you know or your intelligence, it can’t be a demonstration of eloquence or ornamentation. I mean, even when it is those things, they are just the plastic coating over the wire which carries the current from your body to another person’s head. An electric current, generated by the impossibility of love and the inevitability of death and things far crueller than memories. Those who abandoned you, to the point of suicide, what to do with their ghosts, but write? Actually, the idea of any point is an impossibility.

Of course, with time and experience, now that you work as a journalist or otherwise write for a living, there points to be made, after all, some closely defined objectives: to present an argument or tell a story or explore an experience—if not stamping out product on a production line. And with objectives come the techniques—more or less mechanical—to achieve them. But even then that’s only a part of it. Without what happens between the stomach’s mouth and the ribs—and with apologies to thousands of writers whose work is actually popular—there is no meaning to writing and no joy in reading it. If you’re a writer as I understand the word, a moment will have come while you’re speaking, or just afterwards, a moment of panicked discovery when you see that the content of what you’re saying, the things that the words in your texts refer to, do not matter; or rather, they don’t matter until they are referred to by these words of yours, in the form that you’ve created especially for them. Because the whole business lies in what comes next: other words which both illuminate them and cast light forward—and then the thing that results, which accustoms the reader to the distortion of reality and the links between the things the text refers to, and other things, in life.

I realise this seems convoluted, but in my experience, it has the spontaneity and simplicity of physical need. Like thirst or hunger or desire, though rougher and harder to satisfy and, in how it manifests and is realised, more complex than all these things.

After more than twenty-five years in the business of writing, I confess: all it is, is a pain between the stomach’s mouth and the ribcage that makes you forget that there’s no point in words.

It was pain, I think, that drove me to make this the centre of my existence from the age of, at latest, eighteen. A physical pain that comes from mental suffering, the result of a chemical imbalance, or a social void, or any stupid little thing that conceals within it the tragic consciousness of the fleeting life of an individual or of a generation. But what was tormenting me? A life spent between the Cairene neighbourhood of Doqqi on the Nile’s west bank and my school which sat, as I wrote in one of my earliest poems, “in the pyramids’ shade”. I was loved as a boy, yet to understand that my father’s silence and ponderousness, his perpetual sleeping, was depression. True, there was a class difference to be traversed between home and school. There was the anxiety inherited from my mother that I didn’t realise was pathological, and there was lots of chatter in my head I couldn’t understand about History and Truth and The Meaning of Life. When I was nine, I discovered that I was fat. When I was thirteen I travelled by myself for the first time. I had shed the excess weight yet failed to gain the approval I craved from my athletic, rich-kid peers. At sixteen, though, I beat them all when I fell in love with our English geography teacher and she loved me back. At that age life is all ideals and windmills.

I wrote. I would deliberately set out to write, would think about what to write, but the texts that lived were those which welled from some point deep in my chest without me meaning them to, without any prior understanding of what they signified. And without ever being asked to clarify or face questions like, How will you earn enough to eat? or, Is there any point to serious literature at the tail-end of the second millennium? it was apparent to me that this activity was sufficient for meaningful existence, for a life with value. I hadn’t worked out that what really set these texts apart was that they placed reality at their service, rather than serving reality. The complete antithesis of those that deceived and harmed and gave people permission to use each other in ways that seem to me to have grown only stupider and more contemptible between the mid-1990s and the present day.

When I started out, I was completely unaware of this, but I still believe it is the one thing above all others that persuaded me to write: that writing was the one state in which words ruled over things and not the other way around. It was the space in which the tongue is manumitted from its slavish labour on behalf of interests and creeds and loyalties. Even death. “We all have to die a bit every now and then,” as Our Saint Roberto Bolaño says. “And He taught Adam all the names,” says The Most High. The tongue, as interface between consciousness and reality, is the most important thing of all. So it seems to me. It also seems to me that, outside this understanding of writing, the tongue is mistreated and disdained to the utmost degree.

So, I’m going to be a writer. But what does that mean? Will it save me? There were other factors at play.

That I was an only child, given to introversion and introspection. My precocious voyage to study in England, and my shock at life there. My repeated failures, time after time, in different and ever-changing ways, at something I felt was the entire purpose of existence and which, with the exception of that selfsame pain in the selfsame point inside me, I was unable to define, let alone identify: the love whose equal is no less than surrender to death, which appears in the shape of a person. The love which may indeed be irreplaceable no matter how bad it is, but makes you suffer for chancing your life on its whims.

I believe that writing, as I understand it, differs radically from an authorship that meets the conditions of a literary genre or an intellectual cause. More than once, and bitterly, I’ve laughed to see a book of mine judged for its conformity to the rules of a genre it supposedly belong to, or for the moral-political message it is dragooned into delivering. What makes me feel most alienated, I believe, as someone who claims this as their profession, is everyone’s insistence that writing must have a pragmatic use; that the text must express a given position on a given subject, or must sell a certain number of copies, or must fit the part its writer happens to be playing on some virtual platform. And how I’ve come to loathe that profitable trade in identities in the American cultural marketplace.

As I see it, writing is a thing that in its very nature is against being used. It is read, of course, but it does not have to be read with the aim of supporting a point of view or answering a question, nor even to reveal truths the reader may not be able to access elsewhere. It is read to change the shape of life. Is this possible? How possible? I believe that this is what happened to me during the period in which I realised that writing is what I wanted to do with my life.

I read That Smell by Sonallah Ibrahim, and Wagih Ghali’s only novel, Beer In The Snooker Club, and later, at university, Story of the Eye by Georges Bataille, and I was not the same person any more and the world was not the same cramped space it had been. Of course there were many other texts from this period and the years that followed. I read things that completely changed the shape of my life and all I wanted was to distill my own experiences the same way, to change the lives of other people before I had the experience with which to change them. It was then the idea settled in my mind that the process of producing and consuming texts like these was closer to the encounter of two lovers than it is to buying and selling. In love you become someone new. You risk yourself to be with another and the shape of things is changed. And so with writing. In years to come, when I learn that the original meaning of the Arabic word for book is a letter, I will embrace all kinds of epistolary metaphors for what happens when I write and am read by someone I do not know. I will be certain that writing is worthwhile so long as even one person reads me.

I now believe that writing is the most effective path to intimate understanding. Whether face-to-face or through the ether, when words are between you and someone with whom you have a relationship, no matter how good your intentions, the relationship intrudes. There has to be a distance, created by a unique ordering of words selected without complete intentionality, in order for your pain to transform into a window through which your reader may see a new world. And leaving aside its connection with words and speech, it seems to me that writing, like love, is the act of clinging ferociously to life in those moments when death is closer and clearer than any possible purpose. And in the same way that love isn’t porn or songs by Abdel Halim, nor is death hot weeping for the loss of someone you loved. It isn’t funeral rites or mystic pronouncements which, even in their most evolved forms, are controlled by the primitive idiocy of punishment and reward. Death is the black nothing that turns every glance or touch or possibility of encounter into a miraculous treasure whose squandering is the true rejection of the divine. Love is just an awareness of death, and so is writing.

I believe that pain, from the moment it is first felt, through its journey from the writer’s body into a stranger’s mind, to the point at which it turns words into windows, is writing’s most profound content. Of course there’s a subject, of course there’s language, even if the writer does their best to avoid them: there’s always something to be written about; there’s always a way to write it. The irony is that these two things are all that is ever said about any writing—that is, when anything is said at all. Maybe they really are all that can be said, as though a human being is nothing more than a body and its movements, the sounds it makes. But again, subject and language are not much different to the coating round the wire that carries the current. The truer content, though it might never be mentioned in the text, is the pain. The pain of the impossibility of love, of death’s inevitability, of the arrows life rains on our heads as we walk the streets—like the lie of someone whose honesty we gamble on, refusing to see the evidence before our eyes. Bright as the proof is, when we encounter their bodies, when we meet them on street corners like lost angels, we are dazzled by visions of a life better than the one we lead.

The text that has influenced me more than any other in my life, I do not know what it means, not clearly: an angel appears and if you follow it you lose everything unless you follow it to the end. It is the pain of longing for someone who doesn’t pay you the slightest mind, for whose regard you’ve risked the dearest thing you had. The purple pain of the injustice of not getting what you deserve; the green pain of starting a project with dreams of conquering the stars only to end up with part ownership of a sandwich shop. But most important of all is the pain of being. What does it mean to inhabit not place, but time? In my writing at least, and without meaning it, or even being aware of it in the first twenty years of my career, there was a constant attempt to engage with what it might mean to inhabit time as it takes you forward and changes the features of your face, the colour of your hair, the energy you have to give to people and to things; what it means that your presence in time makes you a party to the progress of history, or at least a witness to it.

This experiencing of time, it seems to me, is what sets writing apart and makes it more than simply words, more valuable than a commodity, more pleasurable than the audio-visual product which digital culture has converted into a space of hollowed time, like the time you spend flying between two airports. Writing is time packed full. It derives its morality from its immorality; it achieves compassion, not by flattery or glib misrepresentation, but with a gaze that is concerned only with seeing what is there, uncompromisingly, avoiding all fakery. This, then, is what it means to search for the truth: the objective that attends me whenever I ask myself, in an ironic spirit, Why do you write? or, What does writing mean to you?

I really am searching for the truth. I search for certain words in a style that soothes the thing that bubbles between the mouth of my stomach and ribcage whenever I start to strip my skin before the world. Love before me and a black nothing behind, and in the space between, where my foot stumbles and I fall then stand, or search for a body with which to intersect, an activity worth engaging in. The struggle of my life.

Wow. How do you manage this, Youssef? This intense honesty? You strip your readers’ souls bare too. Thank you for this.

More personal essays like this, Youssef! I'm sure this will touch a nerve, with writers, with readers.