Hangover Reading

I trust you celebrated or otherwise effectively marked the occasion, dear friends—happy new year!

I know I was only just in touch with details of my US tour, which now happily involves none other than Eman Quotah at Politics and Prose in Washington—more updates on Bluesky, Instagram, and Twitter soon—but I feel I have a few other things to share:

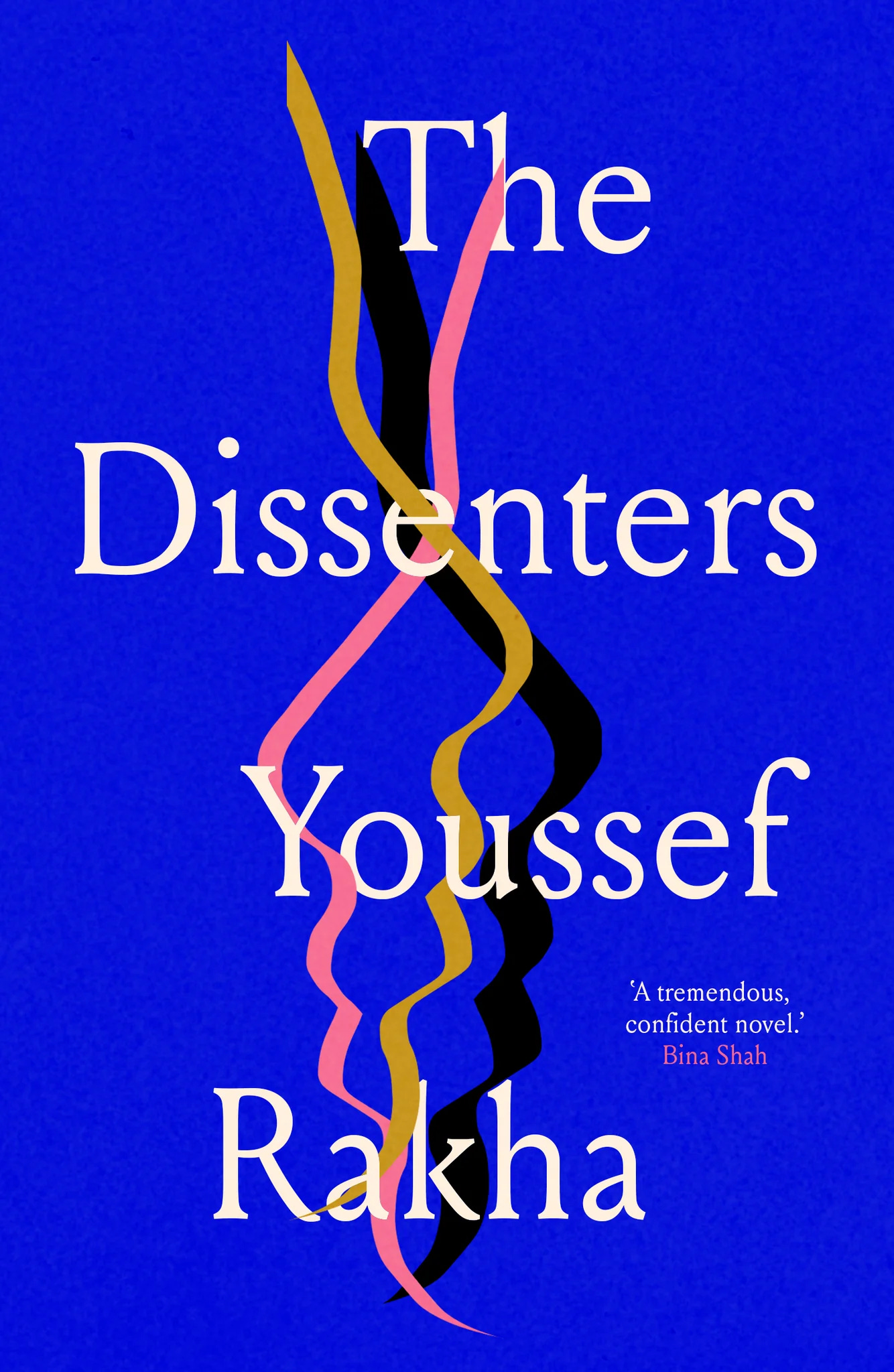

● The Peninsula Press cover of The Dissenters, which I am delighted will be available in the UK (click on image for publisher’s page):

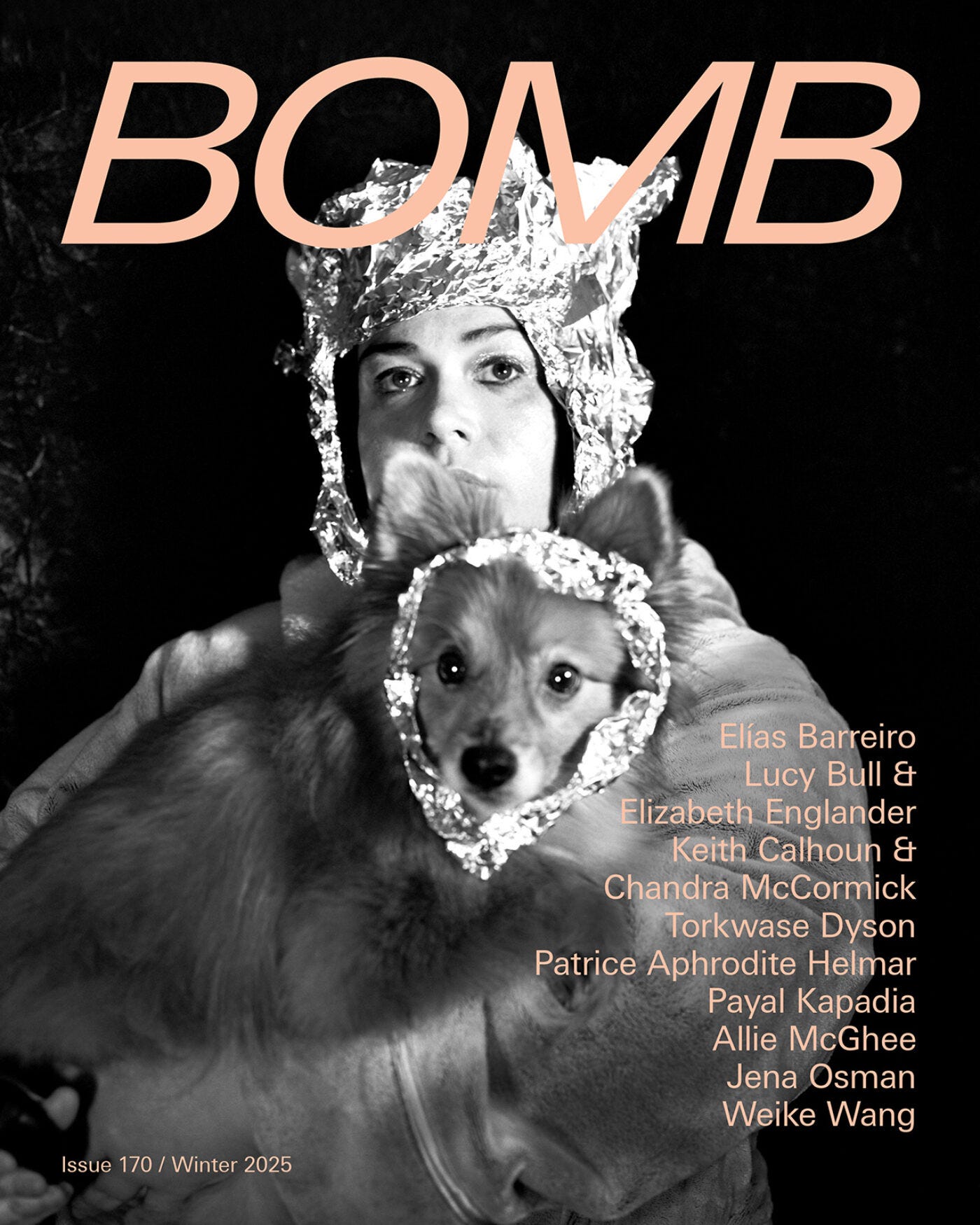

● N. S. Ahmed’s review of The Dissenters in BOMB magazine (it’s paywalled, but that doesn’t mean I’m not sharing it—again, click on the image):

A multi-aliased dissenter—“Nimo” to her revolutionary friends and “Mouna” to her children—Amna falls in with an expansive cast of protesters, lovers, media and political functionaries, and ordinary Egyptians between her arranged marriage in 1956 in the early days of Gamal Adbel Nasser’s presidency and her death in 2015 following Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s appointed tenure two years prior. In the siblings’ conjuring of these tempestuous decades of the Egyptian republic, the personal and the political become umbilically bound in Amna’s story: “So begins a life story or a country’s history, Shimo,” Nour writes to his sister from the attic of their family home, a space of retreat and private rebellion in scenes throughout the novel.

● My wide-ranging, intense conversation with Rémy Ngamije, brilliant author and editor of Doek!, the coolest literary magazine south of the Sahara (click on my image, but read the quote first):

RN: A “sleeper agent in your own life” is probably one of the best descriptions I have encountered about what it means to be a writer. There is truth in the quotation and your interpretation of it: the gradual betrayal of one’s self, the shedding and sharing of privacy, and the eventual disappointment of those around you.

But is that all it means to be a writer? I am thinking about a writer as an ordinary person and the complex, layered roles such a person will have to meaningfully play to be a part of any group or society.

Surely the relationship is not all extractive, is it? If, ultimately, there are all of these betrayals, there have to be some kind of responsibilities that make such intimate betrayals worth it, or justified.

Does writing give nothing back to the agent?

YR: Of course the relationship of the writer to society is not all extractive, although I’d rather replace “society” with “humanity” here—the humanity that is literate in that language—because despite all pretense to the contrary we know societies are ugly, evil things, don’t we?

RN: Oh, that we do, friend.

YR: Perhaps communities can be okay, but that’s not the same thing. At this point in my life I don’t feel answerable to a society any more than I do to a nation or a religious establishment, to be frank—but anyway!

In a sense I think there is more fellow feeling and commitment to our shared humanity in the betrayal than there could ever be in a sincere interpersonal relationship, whether to an individual or a group, especially, of course, to a group, which can be restrictive and peremptory in much more horrible ways. And that’s because you’re hopefully connecting with many more people over a much longer time. But even if you have just one reader or if people are aware of you for only a few days, there is a kind of indirectness or dispassion, a kind of fairness borne of anonymity as well as cerebral and aesthetic imperatives, that surpasses what we are to each other—what we can be. It’s also because there is a discipline there, a sustained practice, which even in its least “committed” variations sustains a sense of accountability.

And finally:

● “The Baghdad Split”, the first of my Postmuslim essays to have been written, which I did mention as an afterthought in the last letter but want to properly highlight today:

I got in next to R. I breathed. He was laughing. He found the sight of me with that plastic bag hilarious. “So you split up just as they went in?” he said as we crossed the Nile back into Tahrir Square, where within hours lines of young people protesting the invasion would stand facing whole regiments of riot police in total silence while Cairo turned into a ghost town, and for a moment I had no idea what he was talking about. Then it all came back.

For eighteen months while putting my psyche back together I had followed the War on Terror. I’d done so for work, but also because I was half-consciously registering how history alienated me from my girlfriend, preventing me from being the Muslim I wanted to be: not a misogynist, homicidal theocrat with a warlike chip on my shoulder but an individual with the right to believe what they choose without having to disown their heritage. This was turning out to be impossible.

I leave you with the following snippet from the only diary I ever kept, for a few months between 2000 and 2001, which I later printed out and had bound—destroying the Word file. I was spending New Year’s Eve in the Bahariya oasis when I wrote this longhand in a notebook before I input it. It is dated December 31, 2000: