A Muslim Medley, and a Markaz Review Conversation

My current project is a series of essays on the theme of identity, and since I want to push things forward, at least in my own mind, I'm sharing five bits of previous, standalone stabs at the topic:

Family lore has it that, at two separate instances during those seven months, [my mother, whose pregnancy with me was a kind of medical miracle] was on the verge of doubting whether she would have her child when she heard verses of the Quran drift through the window, which quelled her fears. On both occasions, it was a verse from the chapter called Youssef, the Quranic story of Joseph, the son of Jacob, not so very different from its earlier version in the Bible.

I was the unlikely foetus, and I quickly learnt to associate whatever state I was in—the intractable mystery of whatever was happening to me as I grew up—with that Quranic chapter. Youssef the chapter is a favourite of professional reciters; you are likely to encounter it wherever and whenever you hear Quran in Cairo. (And you are just as likely to hear Quran wherever and whenever you are in Cairo.) Verses of Youssef are often quoted in print, too. You see them inscribed in bold lettering in the most unlikely of places.

So there was never any reason to believe that encounters with that chapter should bear secret messages. If anything, there was reason to believe that the more I paid attention to such messages, the further ahead on the road to madness I would be. And yet I believed it; I believed it deeply and unreservedly, later seeking to decode the messages I was receiving. Whenever I heard or saw a verse of that chapter, it stopped me in my tracks. It still does, somewhat.

— “Chapter and Verse”, 2008

؏

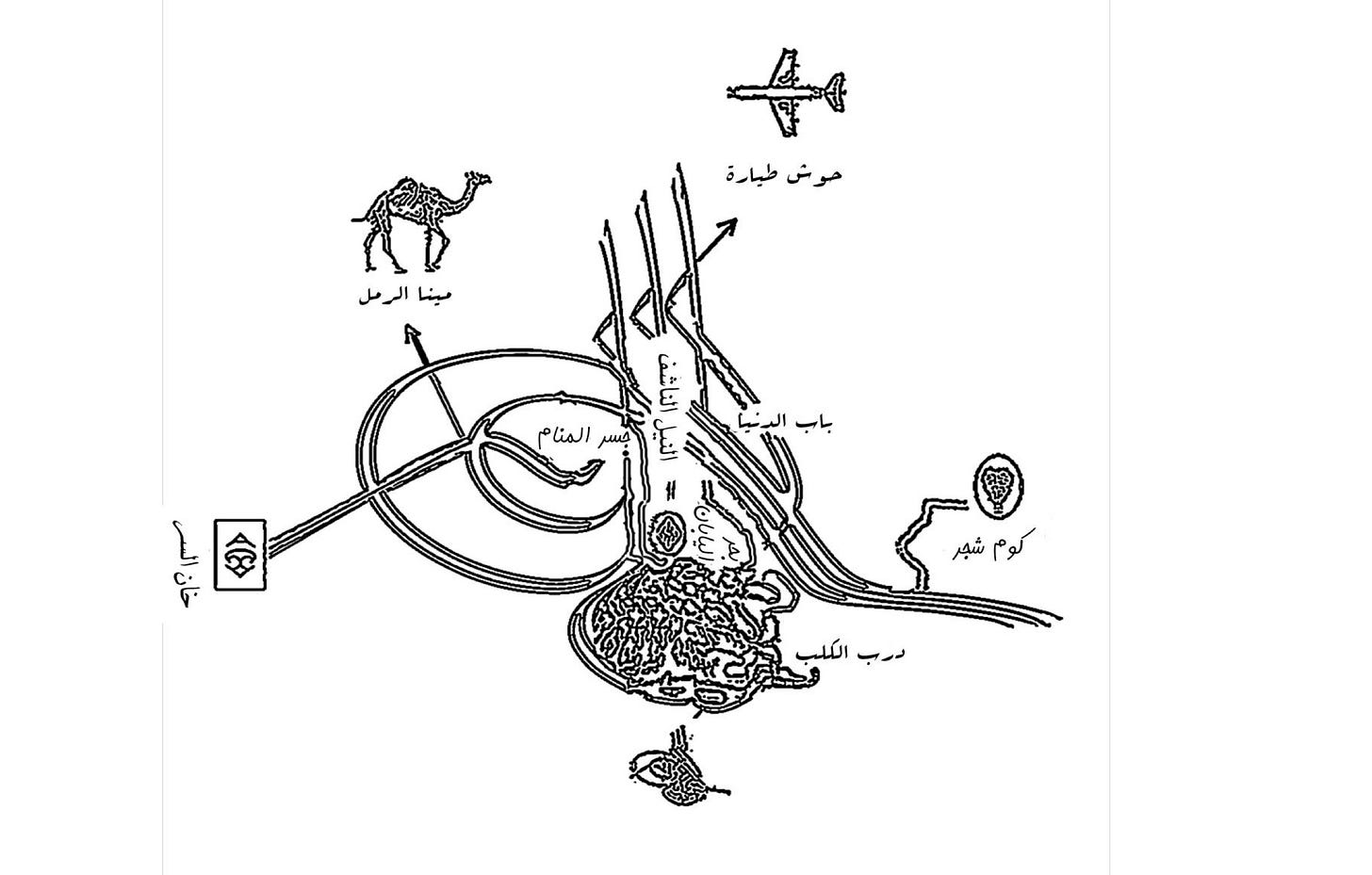

In [THE BOOK OF THE SULTAN’S SEAL] the hero, Mustafa, who will soon start having historical visitations, notably from the last Ottoman sultan, is propelled into rediscovering those parts of the city in which his life comes to have meaning, by drawing the routes he takes as he actually experiences them, with his eyes closed. The shapes that he ends up with later combine to produce a tugra or sultan’s seal—

—which comes to be the symbol of the city as one person’s madness, the city as Mustafa: a calligraphic emblem with many non-empirical references to reality. A sort of psychological form of map-making thus became at the centre of the creative process.

— “Man as Map”, a talk, 2011

؏

More importantly, despite Nasser’s persecution of the Muslim Brothers and despite Sadat subsequently deploying them and other Islamists against socialists and nationalists including Nasserists, neither went beyond [Muhammad Ali] Pasha’s blanket championing of Ottoman (Hanafi) Islam as state creed. This failure to rethink religion, while promptly and repeatedly aborting any attempt at a renaissance within Islamic self-awareness, permitted neither freedom of belief nor a sufficiently literal “application of Sharia” to satisfy fundamentalists (who had initially been seen as heretics rather than extremists but whose apparent moral superiority to the powers that be looked more and more convincing as time passed).

In the absence of sufficient material development and under the weight of various hangups about who “we” really are (both of which prevented the intelligentsia from pursuing an intellectual project capable of engaging enough of the masses or investing society with any sense of purpose), neither Nasser’s quasi-socialist pretensions nor Sadat’s efforts to (re)invent “the morals of the village” gave Egypt a holistic culture or value system with which to live as a (larger and larger) group of humans; hence corruption, incompetence, tyranny—and the hypocrisy that was carried to astonishing extremes under Mubarak.

— “On Fiction and the Caliphate”, 2013

؏

The Enlightenment fuelled all kinds of repulsive affronts: colonialism, nationalism, capitalism. But it also begat completely sexy memes like reason, the empirical method and secularism. Only thanks to these memes does the West look like paradise today. Only in their absence did we start to live in infernos. And it’s time to admit that, whatever we feel about them, memes remain nation-less, race-less. Beyond sectarian affiliation.

The dawn first broke in the realms of Christendom, so the world’s earliest Non-Sectarian Individual ended up a Postchristian. It could’ve been Postanything, really. But if not for that creature’s emergence here, there or somewhere, there would be no antibiotics, psychoanalysis or Whatsapp.

— “The Postmuslim”, 2017

؏

Giving up hashish is like being parted from a person, the person I love more than any other – more, in some ways, than myself.

In the buildup to the millennium, this person opened up vistas. He took me through the winding alleyways of Fatimid Cairo. (For better or worse I can only think of hashish as a he.) Sitting with my back against Mameluke ruins, I was not a middle-class tourist but a sipper of sweet tea in empty lots. To the squeaky sound of early Umm Kulthum songs on a rickety cassette player hanging from a nail in the unpainted wall, I melded into a ring of working-class smokers sharing the vegetal paradise in the dark.

Hashish slowed me down enough to appreciate the opera-like art of Quranic recitation: a single vocal apparatus acting out the holy dramas in sublime musical modes. It’s a magic I’d been deaf to, partly because of its association with funeral rites. But in hashish’s company death isn’t as repulsive as it used to be.

The pigeons wheeling over the minaret-mottled skyline at sunset reconciled me to Egyptianness.

— “Islam and the End of the World”, in THE ORDINARY CHAOS OF BEING HUMAN, 2019